The rise of contact-tracing applications to support the relieve of restrictive measures during COVID-19

An overview of approaches and initiatives for COVID-19 contact-tracing mobile applications in the world and in the EU Member States

Several measures have been taken by countries worldwide to reduce the spread of COVID-19. As some countries start to experience a decrease in the intensity of the spread, the question ‘how to safely go back to normal’ arises. As COVID-19 is not likely to stop being a medical emergency anytime soon, authorities are assessing how they can slowly allow businesses and citizens to resume their ‘normal’ activities, with the virus still being present.

One of the approaches to have a better control of the medical risk of going back to conventional social interactions is the use of contact-tracing mobile apps. These applications aim at providing insight into who may have contracted COVID-19 by monitoring their interaction with others who are a potential risk. This way, the spread of COVID-19 can be more closely monitored both at societal and individual level and adequate actions can be taken. This, in turn, can accelerate the speed at which a country can relieve their restrictive measures.

In this data story we explain how contact-tracing apps collect and use data, and provide visualisations of initiatives for deploying such tools within the EU Member States.

What is a contact-tracing app?

Contact-tracing apps are used to track which citizens have been in proximity to individuals who are a potential vessel for contagion, either because they were positively tested for the virus, or were otherwise diagnosed, or were themselves involved in interactions with others who are sick. Tracking these citizens is useful to measure transmission, as these citizens may have unknowingly contracted COVID-19 during their asymptomatic incubation period. In the past, contact-tracing was mostly carried out manually by human “contact tracers”, attempting to produce the same information through data collected in interviews and painstakingly processing it, which is an extremely time-consuming process, unsuitable to support a fast response. In the current pandemic, the speed and volume by which the virus propagates makes the degree of contact tracing by human tracers nearly unfeasible. Therefore, an automated contact-tracing tool – such as an app running on a mobile phone that almost anybody has in her/his pockets - can provide more efficient and accurate tracing with whom infected people have been in contact. Additionally, the precision and granularity of the data collected automatically by an app used by large parts of a population can better help understand how the virus spreads and empower authorities to respond effectively.

Most of the contact-tracing apps discussed these days in the news make use of low-energy Bluetooth to detect nearby mobile devices, though exact technicalities and functionality differ per application. In principle, the application broadcasts a constantly changing identification key to increase the protection of the privacy of the users. When two mobile phones come in proximity, each app detects the other, announces its key, and records the other’s. If a user associated to one of the two mobile phones ends up being identified as at risk, the information is propagated to the system. Depending on the model being implemented by the app, this information may be either voluntarily by the user or automatically shared with the authorities, e.g. when the user is hospitalised. Upon identifying an individual at risk, all keys broadcasted by her/his mobile phone within a certain number of days (e.g. 14-21, depending on the incubation period) are matched vs the keys collected by other apps in the region. Depending on the model implemented by the app, if a match is found, there will be a response of some kind, that may go from simply warning the people who are affected, to potentially informing the authorities. The app may also be used to administer the right to circulate freely, e.g. citizens may not be allowed outside of their homes unless their apps inform them that they are not a risk to others.

Contact-tracing apps could be provided by both public and private organisations, as well as partnerships thereof. An example of such a partnership is the one announced by Google and Apple, that are working on a re-usable platform on top of which national authorities can develop their own contact-tracing apps.

Contact-tracing app deployment in Eastern Asia

Early deployment of contact tracing technologies has already been an important part of the COVID-19 response of various governments in East Asian countries. According to Harvard Business Review, Singapore, South Korea, and China have implemented apps that include functionality for contact-tracing. Their advancement can be justified by the earlier spread of COVID-19 in their countries, but also to differences in cultural sensitiveness to privacy intrusions (e.g. read https://eudatasharing.eu/news/us-vs-them-vs-data-sharing).

For instance, Singapore launched the app TraceTogether, using which infected individuals can grant the Singaporean Ministry of Health (MOH) access to their proximity data. Granting access allows the MOH to more rapidly contact people who had close contact with the infected individual.

Another example of such an app is the self-quarantine safety protection app, developed by the Ministry of the Interior and Safety of South Korea. By using GPS to keep track of those who have been ordered not to leave their home, the app aims to make sure they keep in contact with case workers and remain in home-quarantine.

Even though the basis of contact-tracing apps is similar in East Asia countries, the integration with other technologies and government resources, as well as data disclosure can differ. When developing apps in the EU, developers can potentially learn from best practices in these countries, keeping a difference in cultural values, privacy standards, and data protection standards in mind.

Initiatives for contact-tracing apps in the EU

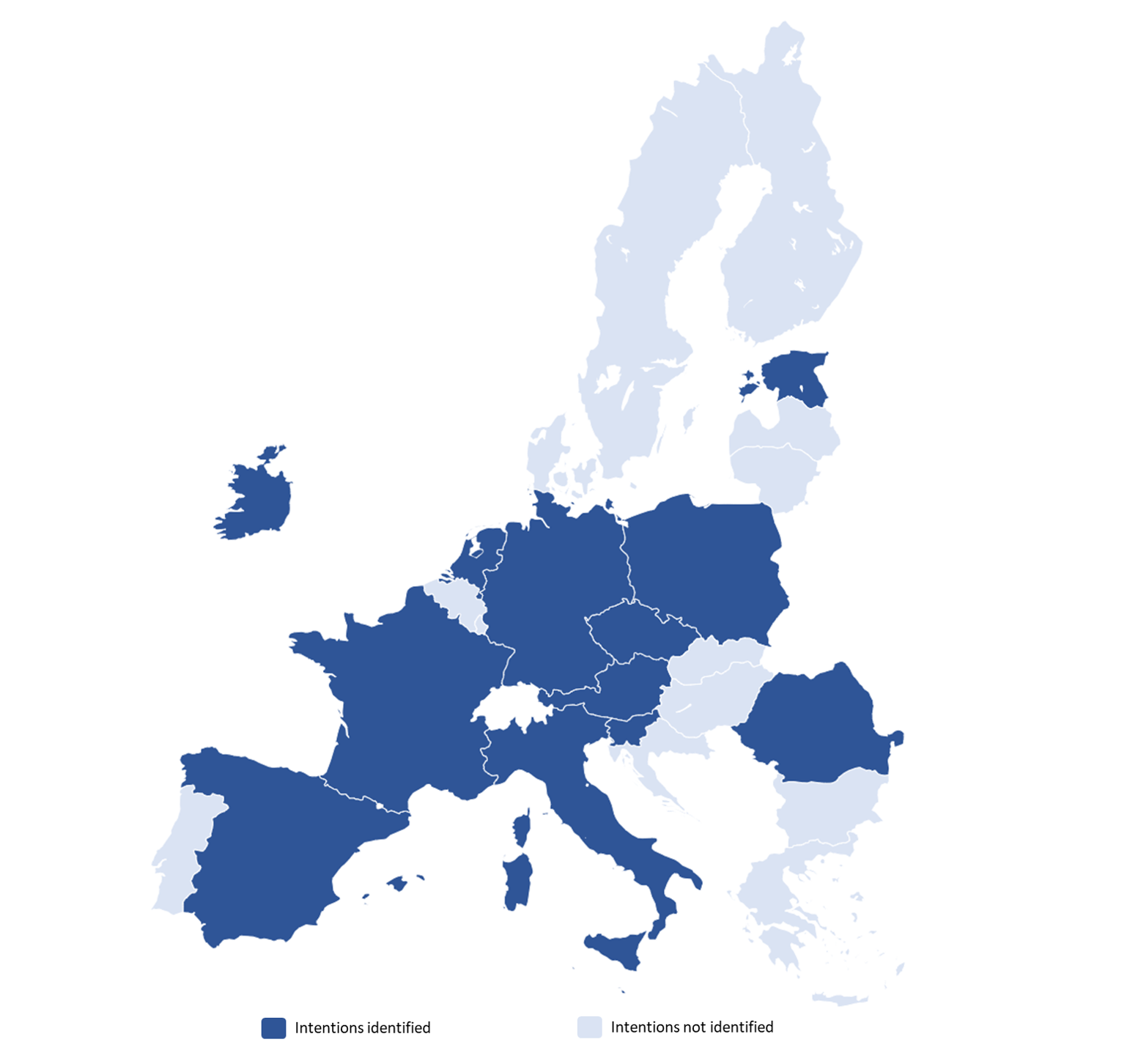

To get a sense of the current developments regarding contact-tracing in Europe, we have investigated which countries have reported intentions to – potentially – start using applications for contact-tracing. In Figure 1 below we show which Member States have initiatives for contact-tracing apps. These visualisations are based on a dataset created for the EDP by our COVID-19 editorial team.

Figure 1. Initiatives for contact-tracing apps per EU MS’ (Last updated: 22 April 2020)

As can be seen from the visual, the Member States are taking initiatives to create solutions in their countries. For instance, the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport organised an appathon which took place on the 18th and 19th of April where solutions from several suppliers are developed, improved, and pitched. As another example, the Ministry of Health of Czech Republic already deployed a contact tracing app as part of the COVID19CZ initiative called eRouška that is GDPR compliant and aims to facilitate the smart quarantine in Czech Republic.

There are also European-wide initiatives, such as PEPP-PT and DP-3T, in which scientists, researchers and technologists develop frameworks to enable development of Pan-European contact tracing apps. The underlying approaches of the initiatives differ in level of centralisation and therefore triggered discussions around data privacy, transparency, and EU tech independence from non-EU corporations.

The European Commission’s “toolbox”

The European Commission (EC) published a “toolbox”, developed in a collaboration with the Member States for the use of mobile applications for contact tracing and COVID-19 warnings on April 16. This toolbox serves as a practical guide for the EU Member States when developing such apps and provides a clear set of requirements for applications of such technologies. This is part of a common coordinated approach to support the gradual lifting of confinement measures, as set out in a Commission Recommendation of 8 April.

In the requirements for these apps, the EC reminds the reader that all apps that will be deployed in Europe should be fully compliant with the EU data protection and privacy rules and should anonymise the data. With this statement, the EC shows that public health and safety are important, though should go hand in hand with the rights of the individuals, whether in normal or extraordinary times. To address this challenge, the EC call for innovative and creative solutions that ensure that the apps will be secure and safe.

Another requirement listed in the toolbox, is that these apps need to be installed voluntarily by their users and disabled by the authorities as soon as the app is no longer needed, e.g. when the respective country fully lifts all restrictions to circulation. As observed in deployments of such apps in East Asia, achieving a sufficient number of voluntary users may be difficult. However, the EC taking a guarantee role might be an incentive for user adoption among citizens.

Lastly, the involvement of the national public health authorities in the development of contact-tracing apps is put forward as a requirement, together with interoperability across EU Member States to ensure the health and safety of the citizens across borders.

Are contact-tracing apps sufficient to stop a pandemic?

Though contact-tracing apps offer important opportunities in the fight against COVID-19, the apps alone cannot reduce its spread. It is necessary that authorities establish a strong COVID-19 response infrastructure, where the contact-tracing app functions as a supporting tool. Widespread testing and diagnosis need to be part of this infrastructure, as data on infected users has to be fed back to the app.

An important element for such apps to be effective in contributing the reduction of spread is depending on the likelihood of the citizens adopting these solutions. Moreover, ensuring that the essential functionalities (e.g. Bluetooth) are designed for a seamless experience and operations. By its nature, not all the citizens in every country will use the app since it requires possession of a modern, smart mobile device (in 2018, smartphone penetration in the EU was between 53% and 82%,). Additionally, public stance towards privacy can influence adoption. The EC points out inclusive design as a foundational principle for contact-tracing apps both for fundamental rights and effectiveness perspectives. The answer to the minimum adoption rate for the apps to be successful is still an ongoing discussion. However, based on the evidence from Singapore and the study by the Oxford University, the EC suggests 60-75 % of minimum adoption rate per population to achieve the desired efficiency. Moreover, a combination between human tracing and the apps is desired, to cover citizens who could be more vulnerable to infection but are less likely to have a smartphone, such as elderly or disabled persons.

Given the voluntary nature of the envisioned apps in the EU, it is important for the governments and/or solution providers to consider the accessibility, inclusiveness, and desirability elements to achieve user adoption of contact-tracing apps, in addition to being fully compliant with the EU data protection and privacy regulations.

Disclaimer: The dataset used to create the visualisations is compiled by the Editorial Team of European Data Portal. The data covers the initiatives that are announced publicly until the 22 April 2020. The dataset only covers initiatives that are noteworthy as news about contact-tracing apps.

Contact details: contact form: https://www.europeandataportal.eu/en/feedback/form

Looking for more open COVID-19 related datasets or initiatives? Visit the EDP for COVID-19 curated lists and follow us on Twitter, Facebook or LinkedIn.