Changes in the labour market

This data story focuses on the fluctuations in employment and the measures that have been taken to support workers in need. Furthermore, a closer look is given on how the crisis is likely to permanently change the labour market after the crisis.

The restrictive measures taken by national governments in response to the pandemic are affecting millions, if not billions, of people’s work-life situation. The major economic consequences of the crisis (also discussed in this data story) can especially be seen in the labour market as the impact is both on the supply side (production) and demand side (consumption) of the economy. Some short-term effects that are already noticeable include massive job losses, reduced working hours of employees, and the measures implemented by governments to financially support struggling companies. Furthermore, most people in Europe are currently working from home, which led to an immediate increase in the take-up of telework and other e-services.

This data story focuses on the fluctuations in employment and the measures that have been taken to support workers in need. Furthermore, a closer look is given on how the crisis is likely to permanently change the labour market after its end.

COVID-19 and Unemployment Rates

The restrictive measures that governments implemented in order to limit the spread of the virus led to major adjustments for companies. Most people need to work from home, mobility and transportation options are limited, and some sectors had to temporarily close their offices completely. The economic impact forced many companies to cut back on number of employees or on their working hours. Unemployment across the European Union is expected to rise to 9% by the end of 2020. This is however a preliminary estimate; evaluating the true economic impact or the resilience of the unemployment levels remains a difficult task as it is nearly impossible to predict the spread of the virus following the ongoing lifting of the restrictions, therefore the risk of further partial or total shutdowns.

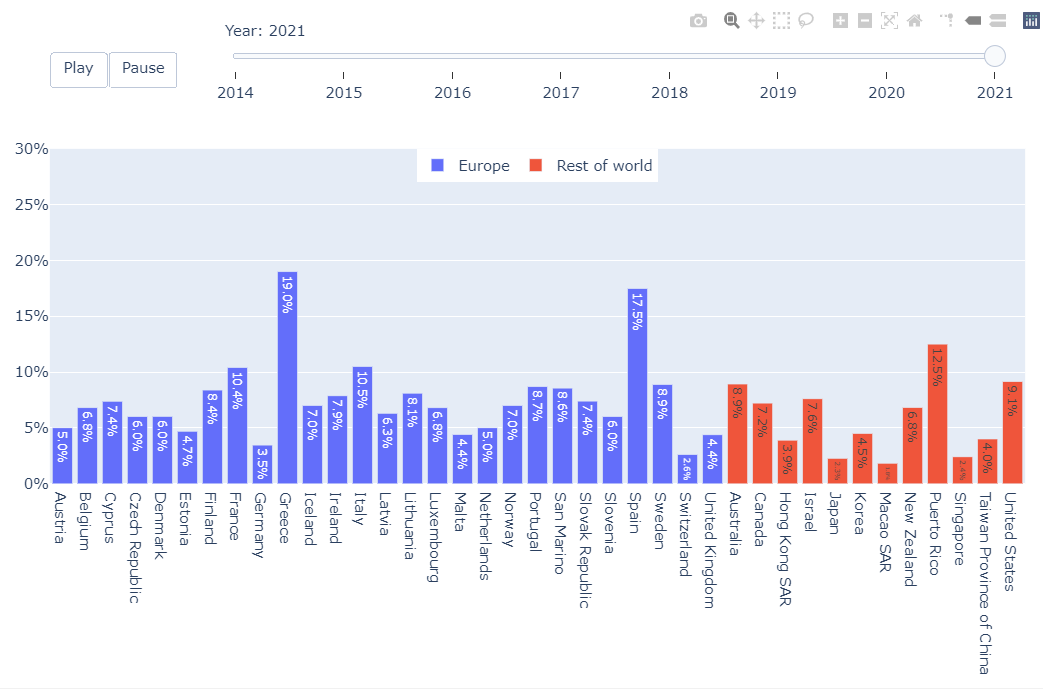

In order to get a better understanding of the unemployment rate and the expected changes in the next two years, the European Data Portal created an interactive visualisation, shown in figure 1, based on the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) World Economic Outlook published in April 2020. It shows the countries with the highest unemployment rates and the changes between 2014 and 2020, including the forecast for 2021.

Figure 1: Screenshot of interactive visualisation on unemployment rates, source: IMF WEO.

Most countries show an employment growth until 2019 and a major inversion of the trend in 2020, which adequately displays the effect the current pandemic. Some of the southern European countries, such as Spain and Greece, already show a higher unemployment rate compared to other countries. For these countries, it can be more difficult to bounce back from the impact of the crisis, as labour demand was already low before.

Several countries, such as Spain, have seen an increase in requests for temporary employment regulations; see for example the datasets of Catalonia, Junta de Castilla y Leon, and Basque country on the European Data Portal. In order to financially support companies to hold on to their employees, the European Union (EU) introduced an emergency support package. The EU adopted a regulation on the temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE), which provides up to €100 billion of loans to EU Member States. This instrument enables Member States to request financial support for the sudden and significant increase of national public expenditure. These expenditures are often due to financial measures such as the support of short-time work schemes and self-employed persons, or health-related measures for workplaces in response to the crisis.

Impact on Labour Market

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency devoted to set labour standards, develop policies, and to devise programmes promoting social justice. In their report published in March 2020, they address the impact that the COVID-19 crisis is likely to have on the international labour market. The impact can be divided in three key elements;

- The quantity of jobs: The ILO estimate a significant global rise of unemployment and underemployment. Unemployment levels are expected to rise between 5.3 and 24.7 million people, based on a best- and worst-case scenario respectively. Moreover, the decrease in labour demand will most likely result in a downward adjustment on wages and working hours.

- The quality of jobs: The decrease in labour supply due to quarantine measures and the drop in economic activity will most likely result in large income losses for workers. This will translate in lower consumption which will disrupt the continuity of businesses and the resilience of the economy. Also, the decrease in income will have a devastating effect on workers that are already close to or below the poverty line.

- The effect on specific groups who are more vulnerable to adverse labour market outcomes: This epidemic can have a disproportionate impact on specific groups of the population and therefore worsen inequality. Groups identified as more vulnerable to the crisis are: elderly and sick people, young professionals and old workers who face unemployment and labour demand issues, women - since they are over-represented in the more affected sectors (e.g. services, healthcare or schools), unprotected self-employed or gig workers, and finally migrant workers.

Related to the third element of the ILO report, another report written by the European Commission about the impact that the COVID-19 confinement measures have on the EU labour market, also estimates that most of southern EU Member States as well as Ireland will be impacted the hardest by the current crisis because of the relatively higher share of sectors that were forced to close. Moreover, especially the most vulnerable segments of the working population will be impacted, such as low-wage workers, women and young professionals.

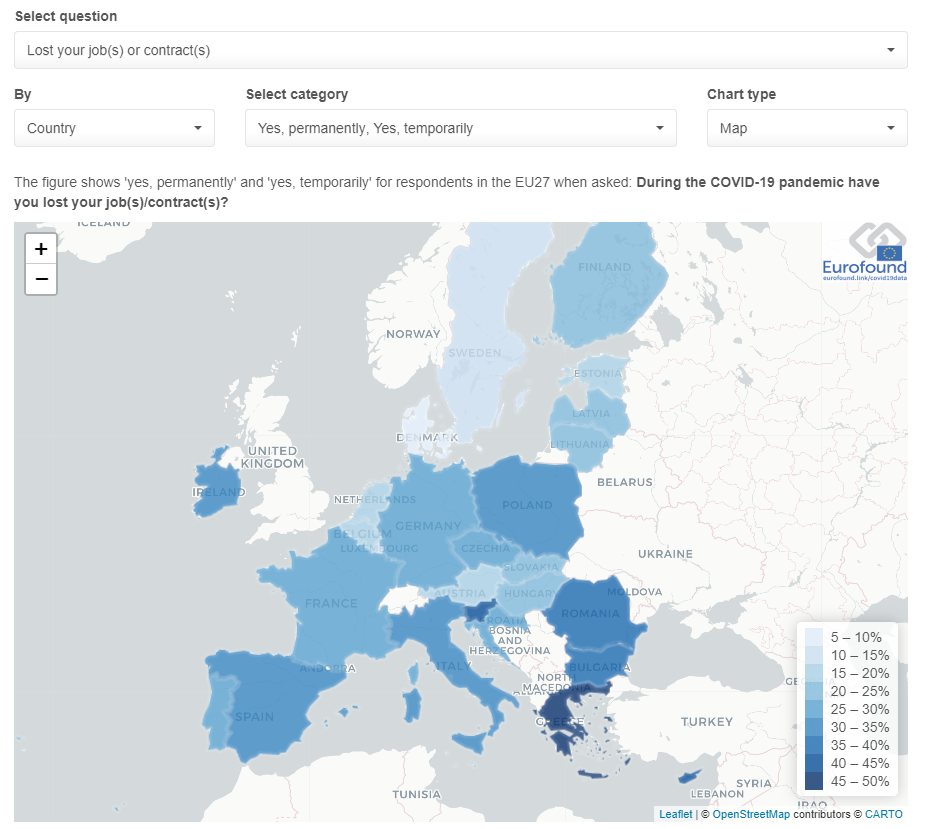

The European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound) is an EU agency with the mission to improve living and working in Europe. In order to capture the immediate changes triggered by the pandemic, Eurofound launched an e-survey called Living, working and COVID-19, last April. The first results on the impact of the pandemic on work and teleworking are visualised in a dashboard and the underlying data is openly available for all the topics. The dashboard covers multiple topics including employment status, working hours, work–life balance, level of teleworking and job security. A screenshot of the dashboard can be found in figure 2.

Figure 2: Dashboard created by Eurofound based on e-survey living, working and COVID-19.

Transformation of the Labour Market

The current crisis caused the labour market to transform. An immediately noticeable change is the sudden switch to a digital workplace where companies and organisations had to impose work-from-home policies. In 2015, research by Eurofound showed that approximately 20% of the European workers did some form of telework, either occasionally of regularly. According to Eurostat, in 2019 only 5.4% of the workers between the age of 15-64 are used work from home regularly. These statistics reflect that working from home was rather uncommon before the pandemic. Some expect that this pandemic will increase teleworking in Europe permanently. A survey held by Global Workplace Analytics shows that 76% of the questioned office workers want to continue to work from home, at least weekly, after the crisis. Unfortunately, some of the countries that are affected harder by the crisis had lower adoption of telework, making it even harder to adjust now or to recover after the crisis.

Besides the increase in working from home, it is expected that this crisis will trigger some permanent changes for the future labour market. It remains a difficult task to predict people’s and businesses’ behaviour when the pandemic is over, but some opinion (e.g. by Politico) already touched upon some interesting transformations:

- This period might be a tipping point for a permanent digital transformation, even after the crisis. With working-from-home policies and keeping a social distance at all time, it is increasingly important that everyone, young and old, possess some digital dexterity. It is currently necessary, for example, in e-ticketing services in public transport, online shopping, and the use of videoconferencing and e-services at work.

- Furthermore, this crisis could result in an increased use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine-learned based technologies. Machine learning already plays an important role in the response to the pandemic. It is, for example, used to study the virus, test potential treatments, diagnose individuals, and analyse the public health impacts. In addition, the European Commission launched an initiative to collect ideas about deployable AI and robotics solutions that could help face the ongoing COVID-19 crisis.

- This crisis could result in an acceleration of the ‘gig economy’ where workers - mostly millennials and young professionals - perform flexible, temporary, or freelance jobs which often involve connecting with clients through online platforms. The gig economy characterises itself with the ability to adapt to the situation, and demands a flexible work and lifestyle, which works well with the freedom that digital work offers and is needed during this crisis. However, working in a gig economy means that the security of a steady job with regular pay, benefits, and a daily routine are rapidly becoming a thing of the past.

- When people will work from home on a regular basis, it could result in an excess of available office space. This in turn could be of use for cities like Amsterdam, Madrid and Rome that struggle with a housing crisis.

- The crisis could result in a different lifestyle for many Europeans, either healthier or not. On the one hand, the restrictive measures forced restaurants to close led to an increase in home cooking and valuation of food, and could result in a change in consumption behaviour. On the other hand, the crisis can result in adverse effects, for example Italians and French gained on average 2kg and 2.5kg during the lockdown respectively. This is mainly caused by eating out of boredom and the increase in consumption of products such as pizza, bread, desserts, and alcohol.

- In addition, people are walking and cycling more nowadays, since it is often the only effective way to move around or exercise. Many European cities are already taking steps to increase cycle and walking opportunities (e.g. Brussels and Milan). If people get used to move around by bike and implement a healthier diet, it could result in a permanent change of lifestyle after the crisis.

Overall, the current crisis, and especially the restrictive measures, have a major impact on the labour market. The European Commission and national governments already implemented several financial measures to support workers and companies that are struggling to survive. However, expectations are that the labour market and the way we work will change permanently. Some possible transformations were mentioned in this data story, but there will probably be more that cannot be predicted today, and we must wait to see what the future holds.

Looking for more open data related news? Visit the EDP news archive and follow us on Twitter or LinkedIn.